Mapping Historic Black Homes

Philadelphia, PA | May 2023

Long-Term Vision

In partnership with the House Museum of Philadelphia, the goal of this project is to:

Compile a list of homes that belonged to notable and influential Black Philadelphians.

Nominate these homes for historic designation.

Preserve, protect, and honor the legacy of notable Black Philadelphians by caring for their homes and providing after-school programs for children at these historical sites.

Background

Philadelphia is a city rich in history—home to the nation’s first university, the birthplace of the American Constitution, a cultural hub during the New Negro Movement, as well as the iconic “Rocky” steps at the Museum of Art, to name a few.

With so many significant sites, it makes sense that the city has established an official Register of Historic Places. This list includes bridges, buildings, and districts, all approved by the Philadelphia Historical Commission (PHC).

Anyone can submit a nomination, and once a property is designated as ‘historic’, it must remain well-maintained and unchanged (unless approved by the PHC). In exchange, site owners benefit from increased property values and guidance on preserving the city’s heritage. The PHC also promotes adaptive reuse of designated properties to balance community needs with historic preservation.

Black Homes as Historic Places

There is a noticeable lack of Black properties included in the city’s Registry and reasons for this have not been provided by PHC. For this project, I hypothesize that one possible factor is the lack of ‘physical distinctiveness’, a key criterion in the designation process.

Systemic racism and discrimination have long impacted every aspect of life for Black Americans, including housing. This may also influence the recognition of architectural styles associated with Black neighborhoods (e.g. row houses). For example, the privilege of having a home deemed ‘significant’ or ‘architecturally' distinct’ according to the standards of the era, was/is not a pleasure afforded to most Black households. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that, of the few Black homes included on the Registry, most have been recognized for the notability of their owners rather than for their architectural features.

Despite this, there are many homes belonging to notable Black Philadelphians that are well-maintained and celebrated by the community, but have not received official recognition. Given the city's rich Black history, majority-Black population, and continued legacy of structural racism that disproportionately impacts Black residents, it is crucial that more Black properties are added to the Registry.

Data & Methods

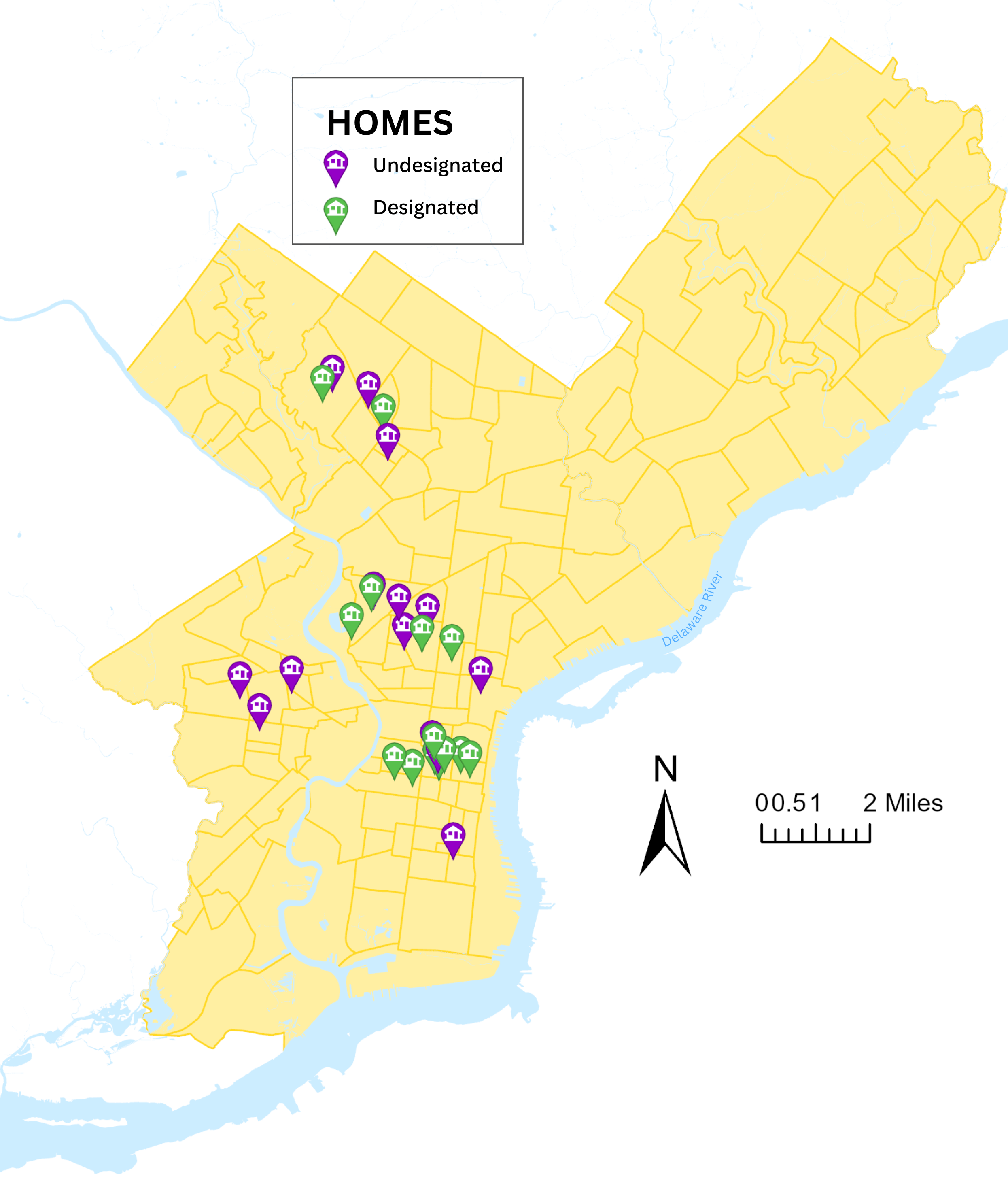

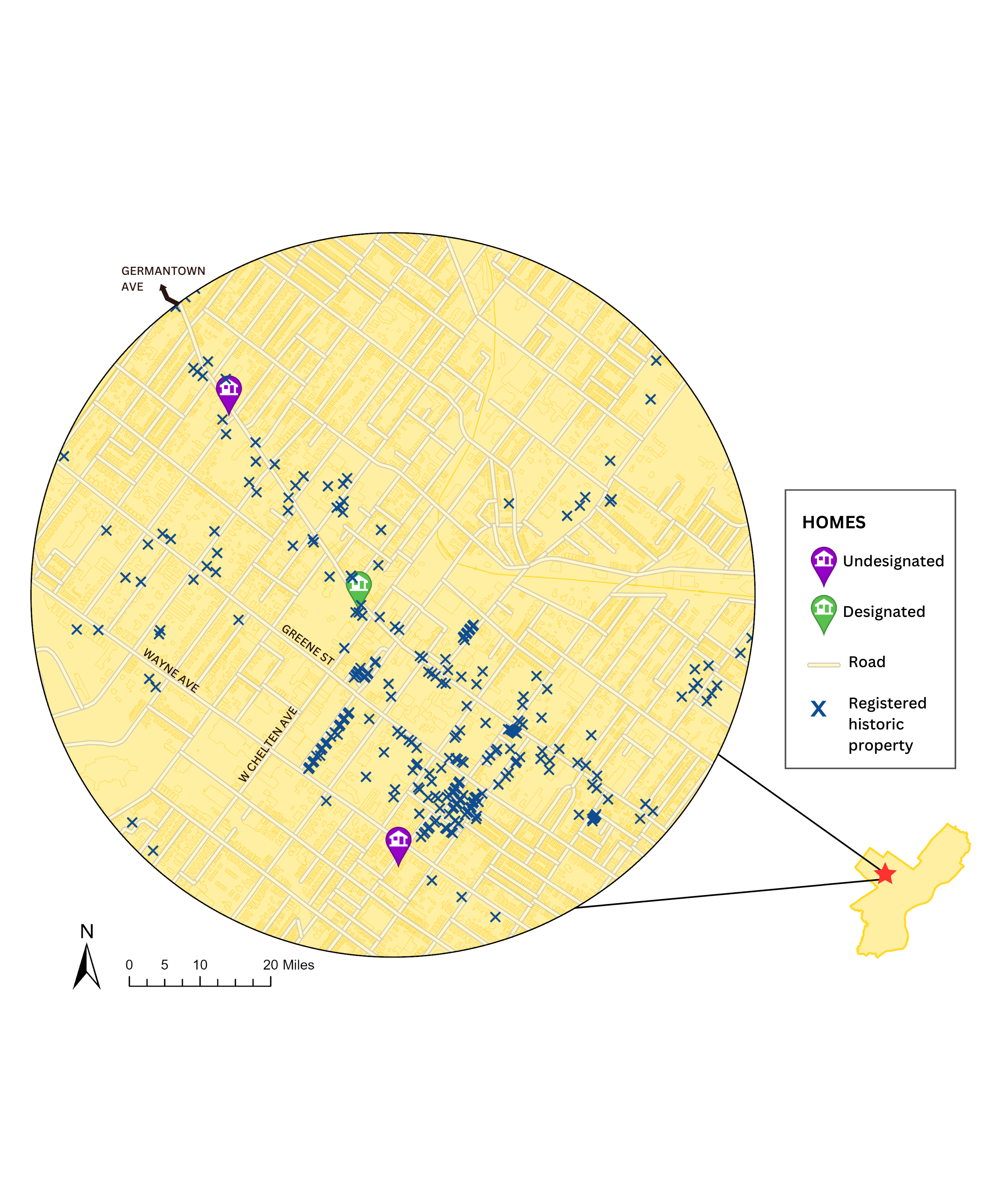

This research involved gathering data from various sources. To start, I accessed the “African American Historic Sites” list from Philadelphia’s Preservation Alliance. After filtering for properties listed as “dwellings,” I matched these addresses with the city’s property database, which gave me a total of 28 home addresses of notable Black Philadelphians. The database also provided information about each home’s value, sale history, size, and current ownership. I paired this information with neighborhood and demographic data (accessed separately) to enhance my analysis.

After, I created an identical dataset for all other homes listed in the official Register of Historical Places.

Finally, using mapping software (ArcGIS Pro), I geocoded the data to generate several maps that showcase the historical and demographic context of these homes.

Challenges

I faced several challenges while doing this research, the biggest one being the lack of attention given to preserving Black spaces in the city. Both the Philadelphia Historical Commission and the city’s Preservation Alliance admitted they could not help me compile a list of important Black homes because the information simply wasn’t kept. This lack of information slowed down my research. Later, when I turned to the “African American Historic Sites” list, I found that many of the original 63 properties listed were not true “dwellings’ or had inaccurate information—in one case, a house that was listed as a “Black” home turned out to be the mansion of an enslaver. After working through these issues, I managed to included 28 homes in my study, but this a very small samples. It represents only a tiny fraction of homes once owned by notable Black Philadelphians that haven’t been officially recognized as historic sites. More research is needed to create a larger and more accurate list.

Maps